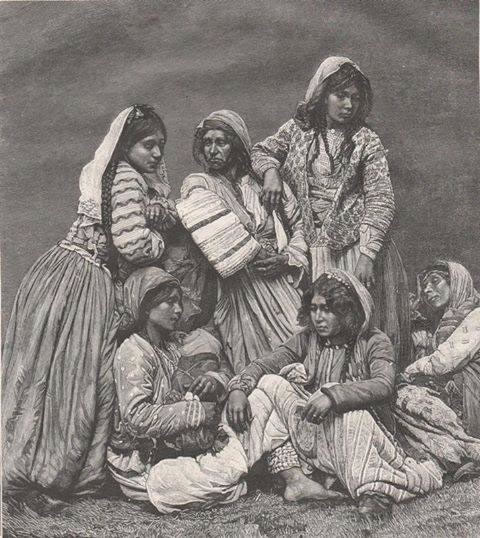

The lotī of Hormozgan trace their spiritual and genealogical lineage to ancient itinerant communities who, some fifteen centuries ago, journeyed westward from the Indian subcontinent across Persia and onward into Europe—communities historically known as Roma, Dom, or Lom. In the Persian Gulf littoral, these performers became known locally as lotī: wandering minstrels, drummers, and dancers whose very livelihood has long been rooted in ṭarab—the craft of musical delight. In coastal towns and mountain villages alike, lotī are called upon to kindle festivity at weddings and seasonal gatherings.

Their performances blend masculine embodiment with the symbolic grace of the feminine: they don voluminous, multi-colored skirts (dāman) typically worn by women, fastening around their waists the jangling dom-e khorusi—a rooster-tail ornament whose tinkling punctuates every turn and step. With the beat of the dehol on one side, the piercing call of the sorna on the other, and the syncopated pulse of the tombak beneath, the lotī animate ritual space, transforming it into a living archive of movement, rhythm, and memory. Though rooted in marginality—often living on society’s fringes as hereditary entertainers—the lotī remain vital cultural transmitters. Their dance is neither staged folklore nor museum relic; it is an embodied history of migration, adaptation, and joy, echoing across centuries from the Ganges to the Persian Gulf.

Kambol (Chamk) Dance of Bandar Abbas: Luti Embodied Heritage

Amidst the searing light of southern Iran, the Luti performers of Bandar Abbas summon an ancient choreography whose memory is woven into every bell, pleat, and swirl. Known locally as Kambol or Chamk, this dance is far more than festive movement: it is a living testament to the embodied musicality of Hormozgan’s marginalized communities.

Dom-e Khorosi & Choreography: A Rhythmic Anatomy

At the heart of this performance is the dam-e khorosi—a “cock’s tail” of weighted, colorful tassels sewn onto the dancers’ wide pleated skirts (læng). Its swing becomes a visible echo of drumbeats, as dancers pivot their hips and whirl, turning cloth into sound.

The choreography is built from compact foot shuffles, quick weight shifts, and dramatic skirt gestures. Dancers clutch the hem, pulling it outward, flicking it inward, allowing the skirt to speak in flourishes that punctuate the pulse of dohol and sorna. Each hip isolation sets the dam-e khorosi trembling, ringing bells on the strong beats. Even without traditional headgear (jelifeh), the dance retains its visual opulence through the moving skirt.

In moments of heightened rhythm, dancers lift the dam-e khorosi higher, intensifying the spiral patterns, syncing with layered polyrhythms that define Bandari music.

Luti Music and Heritage in Hormozgan

The Luti of Hormozgan, often mischaracterized as itinerant performers, trace cultural lineage to ancient South Asian and Roma traditions. In Bandar Abbas and Minab, their dance is not mere entertainment: it is ritual, history, and identity performed.

Generations of Luti families—such as the Novayi ensemble documented by Ali Ettehad—keep the tradition alive. From master Haidar Novayi on sorna to young drummers and dancers, each performer becomes both transmitter and innovator. Together, they sustain a choreography where costume, rhythm, and movement remain indivisible.

This dance historically featured at weddings, religious processions, and seasonal rites, revealing an old performative fluidity: men wearing wide skirts, sometimes stepping into feminine-coded roles, inverting the everyday social order. Today, the skirts remain, but without the ceremonial headbands; yet the dam-e khorosi still beats out the memory of older worlds.

Embodied Memory and Living Archive

Viewed through the lens of ethnomusicology and dance anthropology, Kambol is more than stylized motion. It is an archive encoded in bodies: polyrhythmic footwork, skirt twirls marking melodic cadences, and a dam-e khorosi whose quiver answers the doh-doh pulse.

Ali Ettehad’s travelogue captures this: the humid courtyard; dancers tying lɛngs; laughter as dam-e khorosi is explained; the pride of Haidar Novayi as he offers a final sorna solo. The performers introduce themselves not with grand titles but with ages and family ties—proof that this heritage is lived, not abstract.

In their steps, one finds echoes of distant drums from Gujarat and Sindh, intertwined with Persian Gulf maritime rhythms. It is a dance shaped by migration, trade winds, and devotion.

Instruments in Loti performance

Sorna

Name and Historical Background:

The sorna, also called sarna in local parlance, is a traditional Iranian double-reed woodwind instrument. Its origins trace back centuries, associated with festive rituals, processions, and ceremonies across Iran—especially among southern coastal communities and Baluchi and Bandari musicians. Historically, the sorna accompanied dances, weddings, and religious commemorations, marking moments of communal celebration and lament.

Material, Types, and Sound Production:

Typically crafted from hard woods like mulberry or apricot, the sorna has a conical bore widening into a bell that amplifies its robust, bright sound. The double reed produces a penetrating, reedy timbre, making it ideal for open-air performances. Variations in length and bore shape create different regional tunings and tonal ranges.

Dohol

Name and Historical Background:

The dehol, a large two-headed drum, is an essential component of Iranian and Persian Gulf coastal music. Historically tied to ritual dances, weddings, and social gatherings, the dehol anchors the ensemble with deep, resonant rhythms that guide both dancers and fellow musicians.

Material, Types, and Sound Production:

Constructed from a cylindrical wooden shell, the dehol has animal skin heads stretched on both sides—typically goat or cowhide. It is played with a combination of a thick stick (for the bass side) and a thinner stick or hand (for the treble side), producing both thunderous bass pulses and sharper syncopated strikes.

Tompak (Tombak)

Name and Historical Background:

Known nationally as the tombak and regionally as tempak, this goblet-shaped drum is deeply rooted in Iranian classical and folk traditions. Its role extends beyond rhythm-keeping, adding dynamic ornamentation and improvisational flourishes.

Material, Types, and Sound Production:

Carved from a single piece of walnut or mulberry wood, the tempak features a goatskin drumhead glued to the body. Its hourglass silhouette and light weight allow the player to use fingers and palm techniques to produce a wide tonal palette—from deep bass notes to crisp, high-pitched slaps.

Dialogues in Performance: The Ensemble and the Dance

In the Kambol dance of the Minab Loti ensemble, these three instruments do more than accompany—they converse. The sorna weaves melodic lines with sharp trills and sustained notes, setting a call to motion. The dehol responds with a foundational beat, marking time and summoning the dancers’ footwork and hip turns. The tempak embellishes this dialogue with intricate finger rolls and syncopations, animating the kinetic energy of swirling skirts and shaking dam khorusi tassels.

Together, they create a polyrhythmic landscape where movement and sound mirror each other: the dancers’ steps accentuate the dehol’s pulses, their skirt twirls echo the swirling sorna melodies, and quick shoulder shakes reflect the nimble strikes of the tempak. This interplay transforms the performance into a living, breathing ritual—a dynamic embodiment of coastal Iranian cultural heritage.