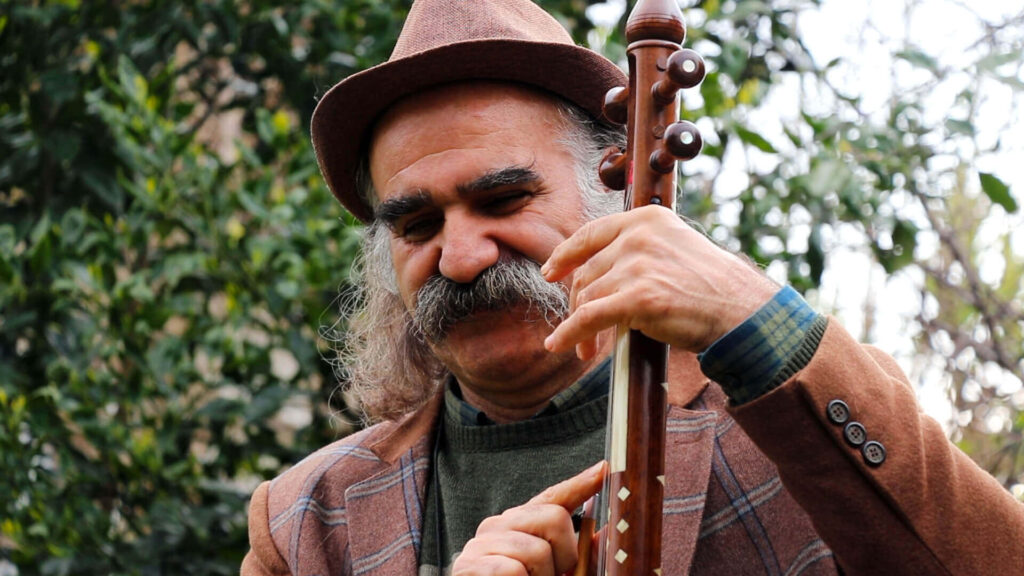

Safar-Ali Ramezani born in 1963 in the village of Payin-Mahalleh Chaparpard, in the Komleh district of Langarud County, is a revered figure in the musical landscape of northern Iran. More than a master of the regional kamancheh (spike fiddle), he is a devoted ethnomusicologist who has dedicated his life to the preservation, transmission, and critical reanimation of the musical traditions of Gilan..

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The Music of Gilan: Soundscapes of a Lush Province

In the northern Iranian province of Gilan, nestled between the Caspian Sea and the mist-laden forests of the Alborz Mountains, music breathes with the rhythm of rainfall, labor, ritual, and lament. The region’s lush ecology, agrarian lifeways, and linguistic diversity have given rise to a complex, orally transmitted musical culture that embodies the affective and ceremonial dimensions of daily life.

Unlike the radif-based classical music of urban Iran, the musical heritage of Gilan is deeply rooted in function and context. From cradle songs to field chants, from festive dance melodies to funerary laments, Gilan’s music constitutes a living archive of the region’s memory, labor, and belief systems.

Vocal Genres: From Cradle to Grave

Gilan is primarily a vocal region, where the sung word holds both narrative and magical force.

Lullabies (lālāʾī) are sung in free meter, often half-whispered, drawing on imagistic language and gently descending motifs to soothe infants.

Sharafshāhī ballads, traditionally performed by itinerant singers accompanied by the reed flute (nāy), recount moral tales and semi-epic narratives in a melismatic, expressive vocal style.

Work songs, especially those sung during rice planting (šālīkārī) or harvesting, maintain steady rhythmic pulses that synchronize collective bodily movement with vocal chant. These chants often feature responsorial forms and refrain structures.

Love songs, such as “Kas nevinam” and “Gole gole,” evoke longing through microtonal vocal tremors and extended glides.

Dirges and laments, often heard during mourning rituals and particularly in ʿAlam-vāčīnī (ritual flag-lowering ceremonies), use weeping vocal timbres and downward scalar motion to express grief.

Instrumentarium: The Rural Orchestra

Although Gilan’s traditional instrumentarium is relatively sparse, its few instruments are employed with great situational precision:

Dohol (double-headed drum) and Sorna (shawm) are foundational to public ceremonies such as weddings, harvest celebrations, and ʿAlam-vāčīnī. The call-and-response between these two creates a rich auditory texture suited to outdoor, communal gatherings.

Karnā (long ceremonial trumpet), used in mountainous areas, announces significant events and is associated with both jubilant and solemn atmospheres.

Dāyereh (frame drum) and tonbak (goblet drum) accompany women’s gatherings and rituals of devotional recitation (ḵatm-e ṣalawāt).

Nāy (reed flute) is employed in solitary or devotional music-making, frequently improvised, and associated with introspection.

Kamāncheh (spiked fiddle) and tombak appear more frequently in urbanized or revived performances, especially in cultural centers such as Rasht or Lahijan.

Ritual Contexts and Musical Function

ʿAlam-vāčīnī, a semi-religious procession, features laments and marsīyeh (passion chants) performed with karnā and dohol, often tied to mourning for Imam Ḥosayn and Shiʿi martyrdom narratives.

Ḵarman-jashn (Harvest Festivals) mark the conclusion of the agricultural cycle and are celebrated with exuberant sorna-dohol duets, collective circle dances, and rhythmic chants that praise abundance.

Weddings are vibrant occasions where percussion and reed instruments dominate, and songs are structured to foster group participation through call-and-response formats.

Rain-invocation rituals, often conducted by children or elder women, involve chanting that borders on incantation—blending folk belief with melodic prayer.

Modality and Rhythmic Structure

Gilan’s vocal repertoire operates within modal systems that are distinct from Persian dastgāh structures. Local melodic contours, sometimes referred to by village musicians as dastān or rah, often make use of tetrachordal progressions and microtonal inflections.

Rhythmic structures tend to be binary (2/4) or ternary (6/8), with an emphasis on asymmetrical pulses in ritual songs. Lamentation songs display free rhythm (āzād), while dance and labor-related songs maintain strong metric frameworks.

Vocal delivery is characterized by ghazālī (tremolo-like) timbres, sharp glottal onsets, and emotional vibrato that approximates crying. Ornamentation is improvisatory and linked to the singer’s affective state rather than formalized patterns.

Geographic Variations: From Talesh to Lahijan

The music of western Gilan, particularly among the Talysh communities, is more rhythmically animated and dance-oriented, while eastern regions like Lahijan and Langarud exhibit more lyrical, melismatic vocal traditions. Dialectal variance in Gileki and Talyshi directly shapes phonetic expression and thus melodic phrasing—extending or compressing syllables in ways that influence musical rhythm.

Safar-Ali Ramezani | Ethnomusicologist, Kamancheh Player, and Custodian of the Vanishing Voices of Gilan

Safar-Ali Ramezani, born in 1963 in the village of Payin-Mahalleh Chaparpard, in the Komleh district of Langarud County, is a revered figure in the musical landscape of northern Iran. More than a master of the regional kamancheh (spike fiddle), he is a devoted ethnomusicologist who has dedicated his life to the preservation, transmission, and critical reanimation of the musical traditions of Gilan.

At a time when oral traditions faced the threat of erasure, with many local melodies either forgotten or reconfigured into popular urban forms, Ramezani chose to become a living archive. Not only does he perform ancient melodies, he delivers them within their full linguistic and cultural contexts—precisely as they were passed down across generations.

To safeguard Gilan’s musical heritage, Ramezani has conducted extensive fieldwork in villages, rituals, and among elder tradition-bearers.

He has collected songs and modal systems absent from written sources, recording and re-performing them to create a living archive of oral music. Beyond performance, he remains committed to intergenerational transmission through informal mentorship, appearing at local ceremonies, and playing music in its native settings.

His work is particularly notable for reviving songs such as “Rana,” “Zarangis,” “Khan Baji,” and “Shurteh,” all of which have undergone rhythmic and melodic alteration over time. Ramezani performs these pieces in their older forms, preserving the original three-line poetic structure and indigenous rhythmic frameworks, then juxtaposes them with their modernized counterparts. As he emphasizes, when indigenous music is reshaped with modern rhythms or tempered Western intervals, it may appear more polished but loses its ontological core—”beautiful, but fake.”

In terms of instrumental organology, Ramezani is an innovator. The Gilan-style kamancheh he plays is distinct: oval-bodied, lacking a heel or tendons, and sharply angled at approximately seventy to seventy-five degrees. The structural modifications influence its resonance, tuning flexibility, and expressive range. In contrast to tendon-mounted instruments with raised bridges, this design allows the pitch to shift dynamically depending on body movement. He explains how the act of playing alters the tuning itself—something impossible on the violin due to its fixed infrastructure.

Moreover, he modifies bows and bridges to revive the raw sonic textures of earlier periods. He handcrafts level bows, twists their hair manually, and occasionally strings the kamancheh with santur wire for greater octave clarity. In doing so, he replicates what he calls the “wild sonority” of antiquity.

Ramezani is also deeply involved in ritual traditions such as Nowruz-e-Bal (the Mountain New Year Fire Festival), Alam-Vachini (the Raising of the Ritual Banners), and Tir-Mah Sizdeh (the Water Festival). He appears not just as a performer, but as a cultural transmitter. In conversation, he resurrects lost concepts like Siyagalesh—the deer and cattle guardian spirit of Gilan’s forests—and links them to Zoroastrian cosmology and Avestaic figures such as Goshurun.

In his worldview, these rituals echo the archaic worship of “vegetal deities”—divine beings who die and return cyclically, bringing fertility back to the earth. He draws cross-cultural comparisons with Tammuz, Adonis, and the Green Man of May Day festivities in Europe, underlining their shared symbolism of death, rebirth, and vegetal resurrection. He references Siawash, the Persian hero whose unjust death gives rise to sacred grasses, and frames these mythologies as living phenomena encoded in song, ceremony, and landscape.

He does not conduct research from behind desks or in libraries. His data is sonic, embodied, and gathered within the flow of festivals and forests. His work is both auditory ethnography and critical heritage preservation.

Safar-Ali Ramezani is best understood as a liminal figure bridging past and present. A custodian of voices on the brink of extinction, his music carries centuries of continuity. Until that final silence, he continues to play in forests and firelit gatherings, offering melodies shaped by generations, carried on the bow of his kamancheh.